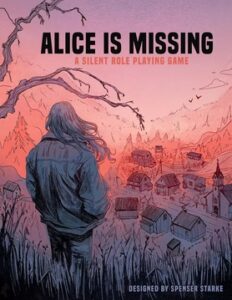

ALICE IS MISSING is a self-contained one-session RPG for 3–5 players, designed by Spenser Stark and released in 2020 by Hunters Entertainment with Renegade Game Studios, after a Kickstarter that raised $138,000. It’s been described as ‘unique’, ‘sublime’ and ‘a little masterpiece’, and has won a bagful of awards including three 2021 Gold ENNIEs and the Indiecade award for tabletop design.

“Just because D&D is behind me does not mean it’s beneath me”

– it took us a while to dig out who said this. We asked around. Vincent Baker said, ‘Not me! Sometimes I say “you don’t get into this business because you hate D&D,” though.’ Jonathan Tweet said, ‘That sounds like something I would have said in the 90s, after I came to appreciate hit points, Armor Class, experience points, and classes’. It turned out to have been S. John Ross, creator of the Risus system, who confirmed it.

SHOW NOTES

These are the notes for this episode, a chance for us to pick up the threads, fill in the blanks, throw up some links, and correct the occasional errors that we didn’t have time to deal with in the episode itself.

The Ford Capri was a good-looking sports-styled car of the 1970s, intended as the European equivalent of the Ford Mustang and designed by a member of the same team. It was used by the UK police, both in reality and TV shows including The Professionals. Its desirability was so high that it was the most stolen car in the UK in the early 1980s. Replaced by the Ford Probe, which is remembered fondly by no one.

The Ford Capri was a good-looking sports-styled car of the 1970s, intended as the European equivalent of the Ford Mustang and designed by a member of the same team. It was used by the UK police, both in reality and TV shows including The Professionals. Its desirability was so high that it was the most stolen car in the UK in the early 1980s. Replaced by the Ford Probe, which is remembered fondly by no one.

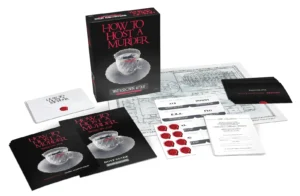

We’ve talked before about Decipher and its How to Host a Murder series (1985–2003), the first roleplay-style games to break through into the mainstream. An evening of scripted larping in a box, they spawned a thousand imitators despite not being actually very good as games. Later entries in the 18-title series included licensed HTHAM games based on Star Trek: The Next Generation and All My Children. Now available again with contemporary styling from Cryptozoic Games, just in time for Christmas.

We’ve talked before about Decipher and its How to Host a Murder series (1985–2003), the first roleplay-style games to break through into the mainstream. An evening of scripted larping in a box, they spawned a thousand imitators despite not being actually very good as games. Later entries in the 18-title series included licensed HTHAM games based on Star Trek: The Next Generation and All My Children. Now available again with contemporary styling from Cryptozoic Games, just in time for Christmas.

Hunter’s Entertainment, the company that publishes Alice is Missing, is a studio that works closely with Renegade Game Studios and Darrington Press, and also co-publishes the Kids on Bikes and Gods of Metal RPG lines, among others. It is led by Chris de la Rosa and Ivan van Norman, who rose to fame as game producer on two series of Wil Wheaton’s Tabletop.

The Alice is Missing digital game (v2.0) is developed by Pixeltable and ‘leverages modern technology to enhance the gameplay experience, offering a seamless and immersive way to connect with friends and delve into the gripping, dramatic narrative’. James, who played it, agrees up to a point: it’s basically a digital version of the tabletop game, without many adjustments for the potential of the technology. More hand-holding in the early stages would have been good. There is also a Roll20 version, if you must.

Brindlewood Bay is the RPG of collaborative murder investigation and talcum powder, which we autopsied in season 3, episode 15.

Puppetland is John Scott Tynes’s ground-breaking 1990s game of playing a puppet in a horrible world of puppets. Originally a free internet download, it is now a beautiful hardback book with contributions from, among many others, Ross and James.

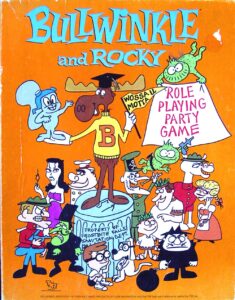

The Bullwinkle & Rocky Role-Playing Party Game was a TSR experimental RPG from 1988, based on a 1960s children’s cartoon largely unknown outside the US. It featured ten glove-puppets, story cards, spinners instead of dice, ahead-of-its-time narrative techniques such as failing-forwards, and much more. Despite innovative design by Dave Cook (Planescape) and Warren Spector (Toon, Deus Ex), it did not find a market and never had a single supplement or a release outside the USA. Rare and collectible these days. To answer the question posed in the episode, it did not use a timer.

The Bullwinkle & Rocky Role-Playing Party Game was a TSR experimental RPG from 1988, based on a 1960s children’s cartoon largely unknown outside the US. It featured ten glove-puppets, story cards, spinners instead of dice, ahead-of-its-time narrative techniques such as failing-forwards, and much more. Despite innovative design by Dave Cook (Planescape) and Warren Spector (Toon, Deus Ex), it did not find a market and never had a single supplement or a release outside the USA. Rare and collectible these days. To answer the question posed in the episode, it did not use a timer.

Leeroy Jenkins was a viral video from 2005, the golden age of MMOs. Specifically, it shows a World of Warcraft raid party discussing strategy outside an area of the instanced dungeon Upper Blackrock Spire known as the Rookery, filled with dragon whelp eggs. This isn’t a particularly hard area as long as you don’t get close enough to the eggs for them to hatch, which is part of the humour for WoW fans: even a mediocre party who knew anything would not screw things up this badly. Although based on a real in-game event, the viral video was in fact scripted and staged, something that should be evident to anyone who’s ever been on a high-level MMO raid.

The Alice Is Missing music is available as a Youtube video that anyone can play. There is a list of all the artists and tracks involved on that Youtube page. A second soundtrack is available to people who backed a Kickstarter, and there are also fan-made soundtracks on Youtube and Spotify. We have not listened to them.

Riverdale is/was an American TV series based loosely on the Archie Comics setting and characters. It lasted for seven seasons with reviews getting steadily worse. Vulture described it as “one of the weirdest teen soaps ever made”.

‘Quarterbacking’ in co-op games is the tendency for one player to take over and direct the other players, either because they have played before and know the strategy, or because they are the loudest. Alice Is Missing avoids it by letting the natural limits of group chats reduce any single player’s ability to dominate the channels. In design terms this is known as constrained communication and has been a feature of co-op games for over a decade, most notably Sky Team, Mysterium, The Crew, Magic Maze, and the two games below:

Hanabi is a game by Antoine Bausa in which players work together to form stacks of cards of the same colour, in numerical order. However, each player holds their cards backwards so they can’t see what they have, and other players must use up resources to give them information, which must follow a constrained format (you can say “These two cards are red” or “Both these cards are twos” but you cannot say “This is a blue three”). Novel enough to win the Spiel des Jahres in 2013, it feels slightly dated today although it’s still great fun and very satisfying when it goes well.

The Mind is Wolfgang Warsch’s card-game of incredibly constrained communication: players must collaboratively play cards from their hand to the table, in the correct lowest-to-highest order, without speaking. The closest thing to telepathy that will set you back the price of a couple of drinks, it is James’s favourite game of this millennium, and he is delighted to find that he is quoted in its Wikipedia article.

Decksandrumsandrockandroll was the only album by British two-piece band the Propellerheads, and was released in 1998. Best known for the tracks Spybreak (The Matrix), Crash (The Spy Who Shagged Me), On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Incredibles trailer), Bang On! (WipeOut 64) History Repeating (There’s Something About Mary) and Take California (the first iPod commercial, 2001), it was infectious and inescapable when it came out, remains the towering pinnacle of the big beat music genre and is one of the definitive soundtracks of the end of the millennium. All just a little bit of history repeating…

Thank you for listening! The hosts of this episode were Ross Payton, Greg Stolze and James Wallis, with audio editing by Ross and show notes by James. We hope you enjoyed it. If anything in this podcast or these notes has spurred your interest then we invite you to come and chat about it on our friendly Discord.

If you click on any of the above links to DriveThruRPG and buy something, Ludonarrative Dissidents will receive a small affiliate fee. You will not be charged more, and the game’s publisher will not receive less, it’s a win-win-win. Thank you for supporting the podcast this way.