MAELSTROM is a paperback-format RPG written by Alex Scott and published in 1984 by Puffin Books, a division of Penguin Books in the UK. It contains rules for roleplaying in Europe, mostly England, at the time of the Tudors (the 1500s), with a solo adventure, a sample adventure and a herbiary. It is an interesting comparison to the other 1980s British RPG set in a faux-Europe of the early Renaissance, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, which was published two years later.

The game was re-released by Arion Games in 2008, and the company has also released an expanded version and several supplements, as well as standalone titles Maelstrom Domesday (set after the Norman invasion), Maelstrom Rome and Maelstrom Gothic.

“The Enlightenment is not equally distributed” – Greg

This episode of Ludonarrative Dissidents is brought to you with thanks to our Kickstarter backers, merch buyers and affiliate-link clickers. Double thanks to people who talk about LND on other forums. It all helps us survive.

>>>>>THE AUDIO FOR THIS EPISODE IS CURRENTLY ONLY AVAILABLE TO THE PODCAST’S BACKERS. WHEN IT GOES PUBLIC, THE LINK TO THE RECORDING WILL APPEAR ON THIS PAGE. TO GET EARLY ACCESS, YOU CAN BECOME A SEASON 3 BACKER BY CLICKING HERE

SHOW NOTES

These are the notes for this episode, a chance for us to pick up the threads, fill in the blanks, throw up some links, and correct the occasional errors that we didn’t have time to deal with in the episode itself.

The RPG Gazette review of Maelstrom and interview with its author Alex Scott.

Another interview with Alex Scott.

The Maelstrom rulebook contains a 160-paragraph solo adventure, which we discussed in the episode. One thing we didn’t note is its use of trap-sections to catch out cheaters who aren’t playing properly, just browsing through. In this case it’s a number of paragraphs that describe a corridor that ‘curves gently to the right’, until you finally reach a sign that says, ‘Reading paragraphs at random brings bad luck’.

The choose-your-path book format dates back to 1930 and Consider the Consequences! by Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins, the first known numbered-paragraph pick-a-path book. It’s the story of a young lady faced with a choice between marrying her impoverished true love and a rich though possibly caddish suitor. Having seen where your choices take her, you then get a chance to relive the story and take it further from the point of view of the true love, and finally as the cad. Filled with interesting emotional and moral choices, it deserves to be better known. It’s also worth highlighting that the form was invented by two women, whose names should be up there alongside the likes of Elizabeth Newberry, Elizabeth Magee, Leslie Scott and Jennell Jaquays as pioneering game designers who were women. You can play an online version of it here.

Warlock magazine was originally published by Penguin Books in 1984 to support the booming Fighting Fantasy fandom. It only lasted thirteen issues in the UK, though in Japan it ran until 1996. Games Workshop took over publishing it with issue 6, shifting editorship to Marc Gascoigne, who printed James’s first professional article in his first issue, and who was later best man at his first wedding. All issues of Warlock are now on the Internet Archive.

Kvetch, mentioned in the podcast, is a lovely member of the Ludonarrative Dissidents community, and was the generous patron for our Dogs in the Vineyard episode earlier this season. He is a fan of Maelstrom and kindly provided physical copies of the original paperback edition of the game for Ross and Greg.

Maelstrom‘s system uses simple percentile rolls against a relevant attribute, from a list of ten, including Attack and Defence. Like many early RPGs it is surprisingly difficult for PCs to succeed at fairly basic tasks if the rules are followed to the letter.

Tunnels & Trolls was the first rules-light RPG, reverse-engineered by designer Ken St Andrew who had heard about Dungeons & Dragons but never seen a copy. First published in 1975, it went through editions at speed, with 5th coming out in 1979. It is mostly noted for three things: its simple, fast d6-based mechanics, its artwork by Liz Danforth, and its extensive range of solo adventures, which made it appealing to Corgi Books, a UK publisher, as a ready-made competitor to the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks. The first UK version, an edited reprint of 5th edition, was released in 1986 (the second will be released by Rebellion later this year). James has a forthcoming article in Secret Passages about the UK pocket-money RPGs of the 1980s.

Runequest was Greg Stafford’s RPG of bronze-age fantasy in the mythic world of Glorantha. Games Workshop reprinted the second edition in a handsome boxed set, and for some years it was one of the default RPGs in the UK.

Stormbringer was an RPG based on Michael Moorcock’s Elric novels, designed by Ken St Andre and Steve Perrin, and published by Chaosium, using its Basic Role Playing system, in 1981. Games Workshop republished the third edition in 1987 as a handsome hardback book, and it did quite well, but by that time there were a lot more games it had to compete against. It’s been unavailable since the licence expired.

Ryan North’s To Be Or Not To Be is a kickstarted solo gamebook from 2013, retelling the story of Hamlet as a solo gamebook, with art by ND ‘Nimona, Lumberjanes‘ Stevenson and others. There are two sequels: Romeo and/or Juliet, and William Shakespeare Punches a Friggin’ Shark and/or Other Stories.

Spotted Dick is a classic British steamed pudding made of suet and dried fruit, usually served with custard. It is hot stodgy comfort food. It wasn’t actually around in Tudor England, at least not by that name. Wikipedia: ‘The dish is first attested in Alexis Soyer’s The Modern Housewife or, Ménagère, published in 1849, in which he described a recipe for “Plum Bolster, or Spotted Dick – Roll out two pounds of paste […] have some Smyrna raisins well washed”.’ Smyrna raisins are awesome.

‘Antagonistic GMing’ is the style of GMing often seen in early RPGs, where the GM is actively working against the players and trying to kill them. Notable examples include killer dungeons like S1: Tomb of Horrors, and the RPG Paranoia. It’s quite frowned on these days except in one-vs-many fantasy-bash board games like Heroquest and Descent. Not to be confused with Agnostic GMing, where the players aren’t sure if the GM is there or not.

What Is Dungeons & Dragons? is a 1982 book from Penguin Books in the UK, describing what Dungeons & Dragons is. In a review at the time James described it as ‘the D&D rulebook without the rules’. It was republished in the US by Warner Books in 1984. As James says in the episode, its three authors were at the same school as him and Alex Scott.

The Cretan Chronicles is a three-book series of solo adventures set in the world of the Greek myths, written by the authors of What Is Dungeons & Dragons?. The books were published by Puffin in 1985–6, in the same line as the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks, but without the promotion. They were well regarded critically.

Greg’s story about the cake-mix that wasn’t popular until the makers required cooks to add an egg is sadly apocryphal: it did happen, but the revised mix sold better because the cakes were nicer when the recipe replaced powdered egg with the real thing. The principle remains that people don’t value what they don’t have to work for.

Early RPGs with actual historical backgrounds instead of fictionalised versions were mostly produced by FGU (Fantasy Games Unlimited). Chivalry & Sorcery (Simbalist and Backhaus, 1977) was set in chivalric France in the 12th century, with magic and monsters and hugely over-complicated rules. Land of the Rising Sun (Lee Gold, 1980) translated the mechanics and structure of C&S into feudal Japan. FGU also published Bushido, the only other RPG set in feudal Japan at the time, so they were competing against themselves, but FGU’s business strategy was always hard to understand.

Attitudes to witches and witchcraft in Tudor England were less extreme than the rest of Europe or the seventeenth century, but all the same if you were proved to be a witch in a court of law then you would be hanged. Burning was for heretics who refused to recant.

Warhammer FRP came out in 1986, published by Games Workshop’s roleplaying department at a time when the company was already beginning to move away from RPGs, It is set in a faux-Europe in the early Renaissance, or more specifically the dying days of the Holy Roman Empire (not holy, not Roman, not much of an empire). Any similarities to Maelstrom are mostly superficial and accidental: The Warhammer world’s style and the key elements of its background had already been set down by the time Maelstrom was published.

Time Lord, the Doctor Who RPG by Ian Marsh, was published by Virgin Books in 1991 (not to be confused with Timelords, the time-travelling RPG by Greg Porter). It used to be a free download from the web but the page has decayed.

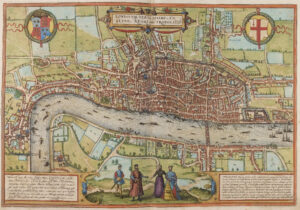

London in Tudor times had a population of around 50,000 in 1500, growing to over 200,000 by the end of that century. It was mostly centred around the old City of London, the area within the city walls (click the map to enlarge), but was beginning to spread westwards and northwards, encompassing existing settlements and villages as it grew. The river had one bridge and occasionally froze so thoroughly that ice fairs were held on its surface. The plague hit the city regularly: in 1563 it killed 17,404 Londoners. (For comparison, in two years the Covid pandemic killed just over 20,000 Londoners, in a city of ten million.)

London in Tudor times had a population of around 50,000 in 1500, growing to over 200,000 by the end of that century. It was mostly centred around the old City of London, the area within the city walls (click the map to enlarge), but was beginning to spread westwards and northwards, encompassing existing settlements and villages as it grew. The river had one bridge and occasionally froze so thoroughly that ice fairs were held on its surface. The plague hit the city regularly: in 1563 it killed 17,404 Londoners. (For comparison, in two years the Covid pandemic killed just over 20,000 Londoners, in a city of ten million.)

James mentions B-format books. In the UK there are three standard sizes for paperback books: A-format (regular mass-market), B-format (larger, the size of Penguin Classics, what the US would call ‘small trade paperback’) and C-format, which is almost exactly the same size as half a sheet of US letter paper.

Time Bandits, Jabberwocky and Monty Python and the Holy Grail were three of the most notable fantasy films that came out of the UK in the early 1980s, along with Hawk the Slayer (below) and Excalibur, John Boorman’s wildly over the top retelling of the Arthurian cycle. The latter was financed by US film company Orion Pictures, the first three largely by British musicians, notably former Beatle George Harrison and his company Handmade Films (Harrison famously put up £3m to cover the production of Life of Brian because he “wanted to see the movie”) and a cricket team.

Hawk the Slayer was made in 1980 by a small British crew with not very much money. It is not awful but it certainly isn’t good. All rights to it are now owned by the games company Rebellion, which has released one new Hawk graphic novel (written by Garth Ennis) but seems to have no interest in a HtS RPG. Ask James how he knows.

Why is Saturn 3 so bad? Many reasons: an inexperienced director, an undercooked script, a slashed production budget (due to overruns on Raise the Titanic, made by the same company, which went massively over budget), a headstrong star, and the fact that nobody really seemed to know what they were making. “One hopes the producers and directors working the genre will realize this audience demands more than a leggy blond being chased by a robot. They may have such limited visions, but the audience doesn’t,” commented the reviewer for the games magazine Ares. Parts of Martin Amis’s breakthrough novel, Money, are based on the production of Saturn 3.

Kingsley Amis, Martin Amis’s father, had been a big champion of science fiction in the 1960s. He was a fan of SF authors including Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth, and edited a series of SF anthologies called Spectrum, mostly very good.

After Saturn 3 Martin Amis never wrote anything that could be described as SF (Time’s Arrow tangentially, perhaps), though he had apparently “read nothing but science fiction till he was fifteen or sixteen” and reviewed SF books for the Observer in the early 1970s. In 1982 he wrote a non-fiction book about video games, Invasion of the Space Invaders, with a foreword by Steven Spielberg. It is very dorky and used to be rare and valuable until it was republished in 2018.

Regarding Mage‘s vulgar magic and coincidental magic systems: I don’t think we can say anything better or more succinct than Wikipedia: “A character’s magical expertise is described by allocating points to nine different “Spheres” of magical knowledge and influence: Correspondence, Entropy, Forces, Life, Mind, Matter, Prime, Spirit, and Time. Magical effects are largely spontaneously proposed by players and adjudicated by the game master, informed by the level of ‘expertise’ in the relevant Spheres of the effect.”

Lucky Day by Chuck Tingle is the third mainstream novel by the beloved writer of gay pornographic ebooks. This one is less well loved than his other titles.

Citybook 1: Butcher, Baker, Candlestick Maker (1982) is a book James has frothed about before: an early work in describing an RPG city as independent but linked locations, characters and encounters not confined to a map. Absolutely worth whatever pittance they’re charging for it these days.

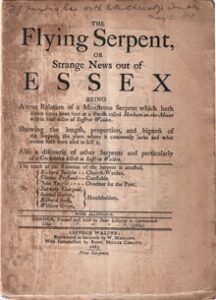

The Flying Serpent, or Strange News out of Essex was first published in 1669, one of the hundreds of ephemeral pamphlets printed each year containing news, opinion, poetry, and popular entertainment. A facsimile was released in the late 19th century. A few years ago James acquired a copy of this facsimile, digitised it and put it up on DriveThruRPG as a PDF, where almost nobody bought it apart from a writer, Sarah Perry, who based her bestselling novel The Essex Serpent (later a TV series) on it. Funny old world.

The Flying Serpent, or Strange News out of Essex was first published in 1669, one of the hundreds of ephemeral pamphlets printed each year containing news, opinion, poetry, and popular entertainment. A facsimile was released in the late 19th century. A few years ago James acquired a copy of this facsimile, digitised it and put it up on DriveThruRPG as a PDF, where almost nobody bought it apart from a writer, Sarah Perry, who based her bestselling novel The Essex Serpent (later a TV series) on it. Funny old world.

(“Oh come on, James,” I hear you say, “isn’t that pushing our credibility a bit?” Perry discussed it in a blogpost on the British Library website, sadly not currently available, but if you compare the woodcut of the serpent on this page with the blemishes on the page in the PDF that I uploaded to DTRPG, you’ll see they’re identical.)

‘Picaresque’ adventures are as old as storytelling, but as novels they date from the 1500s. Episodic fiction about a rogueish and unreliable but likeable character, often based around an extended journey, they are often comedic or even satiric. Notable picaresque works include Don Quixote, Tom Jones, The Pickwick Papers (and now you know why it’s called that), and the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser novels.

Maelstrom‘s cover price was £1.95 in 1984, which would be £6.43 in December 2025 prices, or $8.84. That’s below the price of a typical paperback today and far less than most RPGs cost, then and now, though at the time of writing the US dollar has been in a slow collapse since Jan 2025 and exchange rates are improving (or worsening depending on your perspective) daily.

Bury St Edmunds, where chunks of the recent edition of Maelstrom are set, has a rich background that’s both historical and mythic. James mentions that his mother used to live in a house built into the ruins of the old Abbey (now known as the West Front): in this picture it’s the one in the arch, with the green door. The roof leaked and the garden was overhung by half of a medieval stone arch, threatening to collapse at any time, but it had been there for at least five centuries and might well last the same again. Below it is a picture of what the Abbey looked like at the height of its influence in the fifteenth century, for comparison.

A few miles down the road from Bury St Edmunds is Kentwell Hall, a Tudor manor house that every summer invites around two hundred re-enactors to live a Tudor lifestyle in the house and grounds. It could almost be a Maelstrom larp.

RPGs based primarily on American history: there are Colonial Gothic and The Old West, and that’s about all that comes to mind. If you know of more, please let us know on the Discord and we’ll update this entry. (Update: Ethan Cordray suggests Nations and Cannons, a quite recent product; Carolina Death Crawl from Bully Pulpit Games; and Steal Away Jordan, about slavery and escaping it. Lyme brought up Times That Fry Men’s Souls and Beecher’s Bibles.)

‘Failing funward’, Greg’s version of ‘failing forward’, is so good that I’m nicking it wholesale for Dandy. With attribution.

Chaosium’s Worlds of Wonder was a boxed set from 1982, containing the Basic Role-Playing rules as well as Magic World, Future World and Superworld (later released as a standalone superhero system), as a well as a city setting that allowed characters to move between the different universes. Although fairly bare bones, it is considered the first multi-RPG product.

The herb section in Maelstrom is taken from medieveal herbiaries (James remembers sitting with Alex during one research session in the college library, looking at related books like early printed versions of Pliny’s Natural History, which is a banger if you ever want inspiration for a slightly bonkers fantasy game.)

The Cooler with William H Macy is a 2003 movie directed by Wayne Kramer, about a man whose bad luck is contagious. It is charming and witty, with an Oscar-nominated performance by Alec Baldwin.

Intacto is a 2001 Spanish film directed by Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, about an underground trade in luck. Like The Cooler it is centred around a casino and posits that different people have different innate levels of luck, which can be affected and transferred to others. Great ideas, some fantastic set-pieces that could be great RPG fodder.

The character Domino first appeared in the Marvel universe in 1992 and is best known as a member of X-Force and for appearing in Deadpool 2. She can affect the probability of events within her line of sight.

Thank you for listening! The hosts of this episode were Ross Payton, Greg Stolze and James Wallis, with audio editing by Ross and show notes by James. We hope you enjoyed it. If anything in this podcast or these notes has spurred your interest then we invite you to come and chat about it on our friendly Discord.

If you click on any of the above links to DriveThruRPG and buy something, Ludonarrative Dissidents will receive a small affiliate fee. You will not be charged more, and the game’s publisher will not receive less, it’s a win-win-win. Thank you for supporting the podcast this way.